● A Story of Rebellion, Trade, and the Birth of Nigeria

Many Nigerians know that the country was born out of a business deal, but few know the gripping details of the events that led to it.

This is the story of how one man’s defiance changed history. How King Frederick William Koko Mingi VIII of Nembe waged war against the Royal Niger Company (RNC), an act that would ultimately lead to Britain’s purchase of Nigeria for £865,000 which is roughly ₦281 billion today.

In the Ada-Ama community of Twon-Brass Kingdom, Brass Local Government Area of Bayelsa State, lies a haunting piece of land known as the “White Man’s Graveyard.” This cemetery holds the remains of British soldiers who perished during the Akassa Assault of 1895; a bloody conflict born from betrayal, trade monopoly, and the rage of a defiant Ijaw king.

The story begins with a British trading enterprise.

Founded in 1832 as the African Steamship Company by explorer Richard Lander and 49 others, the firm established its first trading post where the Niger and Benue rivers meet in present-day North Central Nigeria.

Most of the original members died of fever or wounds, but survivor Macgregor Laird continued funding expeditions until his death in 1861.

By 1863, the company became the West African Company (WAC), though competition soon grew fierce. Then came George Goldie, an ambitious colonial administrator, who arrived in the Niger Delta in 1877. Goldie proposed merging all rival British firms into one powerful company.

By 1879, he had successfully combined WAC, the Central African Company, and others into a single monopoly – the United African Company.

To fend off competition from French and Senegalese traders, Goldie sought a royal charter from the British Crown, which would give him exclusive trading rights. In 1885, after the Berlin Conference formalized colonial claims in Africa, Goldie’s company controlled over 30 trading posts along the Niger.

A year later, it became the Royal Niger Company (RNC); a corporation empowered by the Crown to rule and trade across the Niger and Benue territories, free from competition. Armed with royal authority, Goldie and his agents began signing treaties with local rulers most of whom were unaware of the true contents due to language barriers.

These agreements effectively handed control of trade and taxation to the RNC. Chiefs and kings who thought they were ensuring prosperity found themselves locked out of the global palm oil market, forced to trade only through RNC intermediaries.

As profits dwindled and livelihoods suffered, resentment brewed across the Niger Delta.

And in Nembe, one man decided enough was enough.

Frederick William Koko Mingi VIII, known simply as King Koko, was once a Christian convert and schoolteacher who later returned to his traditional faith after witnessing British deceit. As the ruler of Nembe, he joined forces with neighbouring Okpoma chiefs to resist the RNC’s trade monopoly.

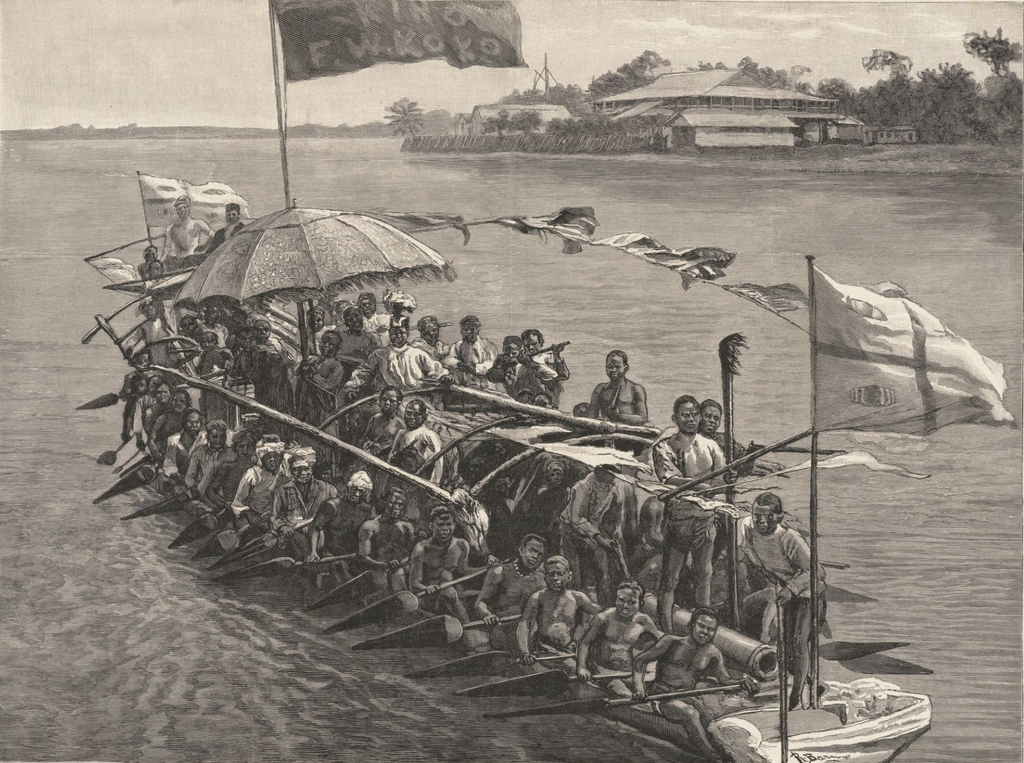

On January 29, 1895, King Koko launched a daring assault on the RNC’s headquarters in Akassa, present-day Bayelsa. He led 22 war canoes and 1,500 warriors, overwhelming British forces. The attackers destroyed warehouses, offices, and depots, razing the entire station.

In the aftermath, 70 men were captured, 25 killed, and 32 British hostages taken. Some were later executed on “Sacrifice Island” when negotiations failed.

Koko demanded that the RNC lift its trade restrictions in exchange for the hostages’ release. When the British refused, he ordered the execution of 40 captives; a fatal statement of defiance.

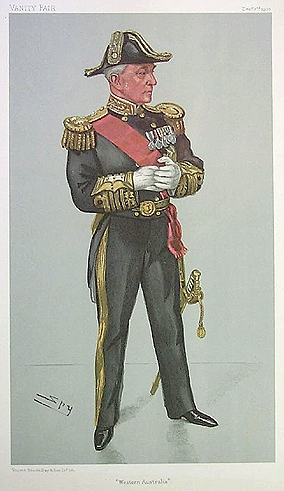

On February 20, 1895, the British Royal Navy retaliated with brutal force. Rear Admiral Sir Frederick Bedford led an assault on Nembe, killing hundreds and burning the town to ashes.

By 1896, when King Koko refused British settlement terms, he was declared an outlaw and a bounty of £200 was placed on his head.

He fled into hiding in Etiema, a remote village, where he reportedly died by suicide in 1898.

The massacre at Nembe and the RNC’s oppressive practices sparked outrage even in Britain.

By 1899, the British government revoked the company’s charter and forced it to sell all holdings and territories to the Crown for £865,000, which was the transaction that officially transferred control of the Nigerian territories to the British Empire.

That sum roughly ₦281 billion in today’s currency was the price of Nigeria’s creation.

The Royal Niger Company may have vanished in name, but not in spirit. Its corporate successor lives on as Unilever Nigeria, a quiet reminder of how commerce, greed, and rebellion once shaped the destiny of a nation.

And in Twon-Brass, the “White Man’s Graveyard” still stands as a silent testimony to the courage of King Koko, the Nembe warriors, and the cost of resistance against the British empire.